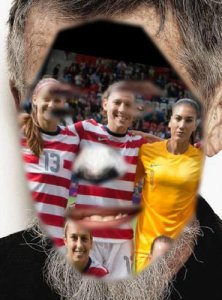

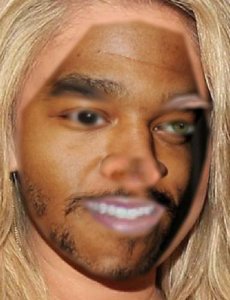

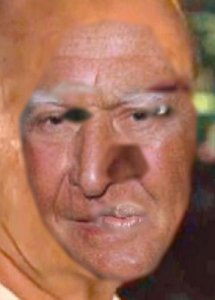

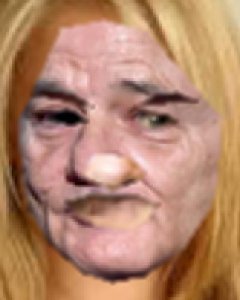

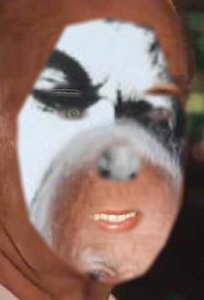

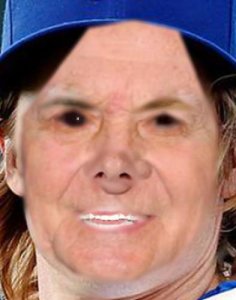

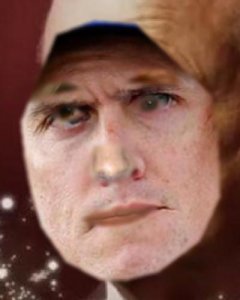

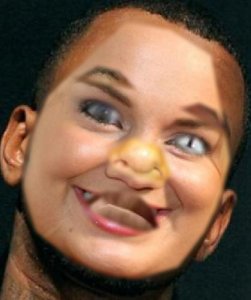

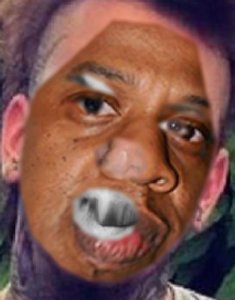

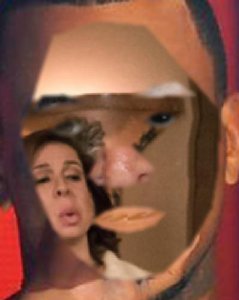

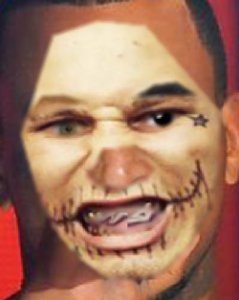

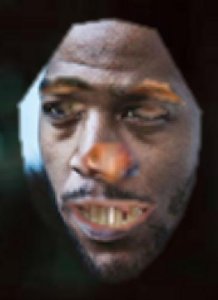

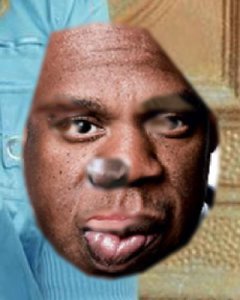

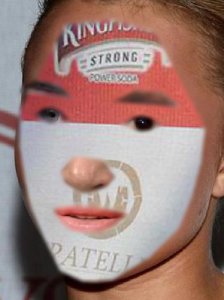

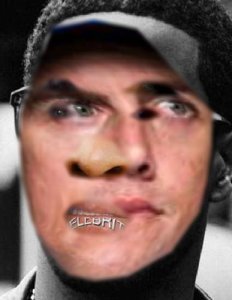

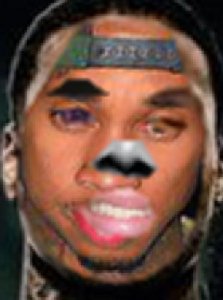

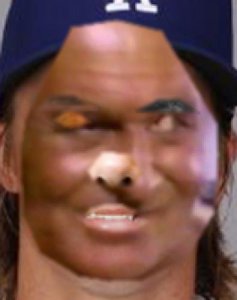

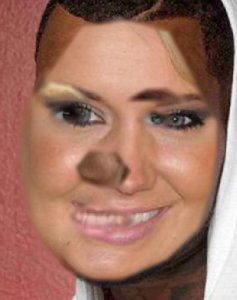

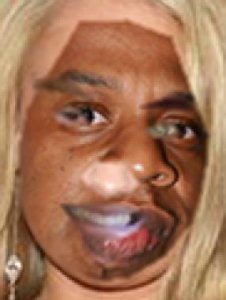

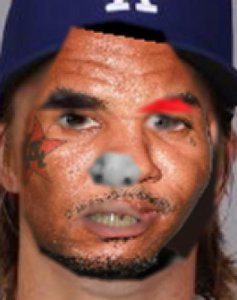

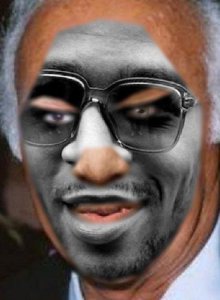

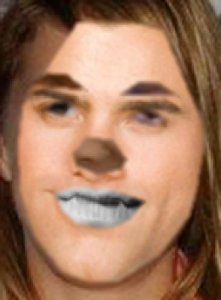

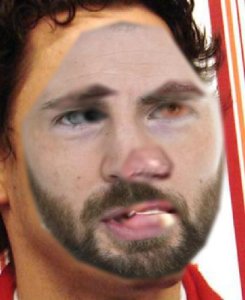

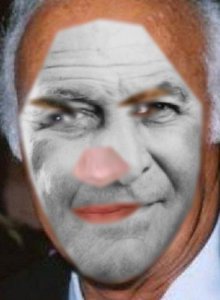

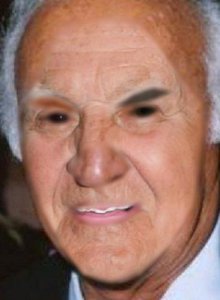

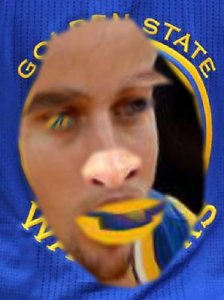

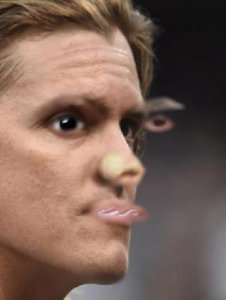

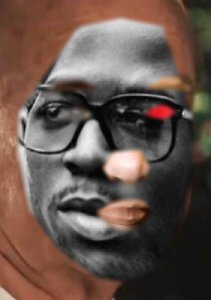

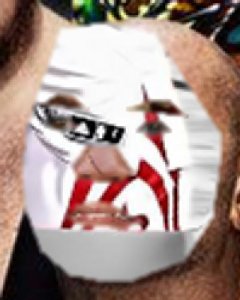

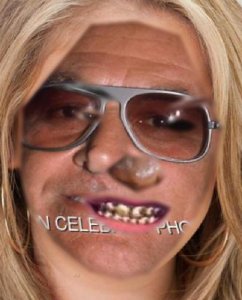

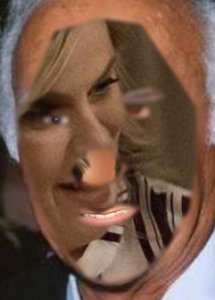

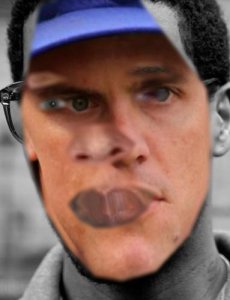

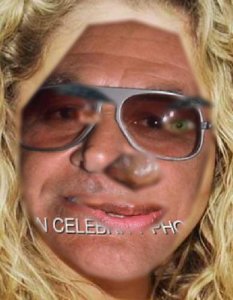

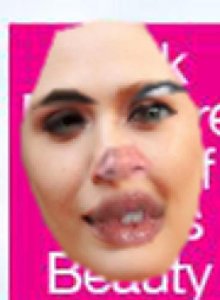

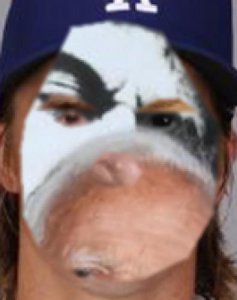

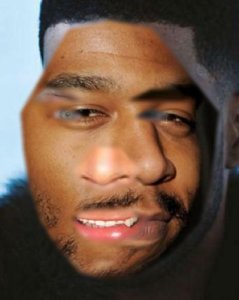

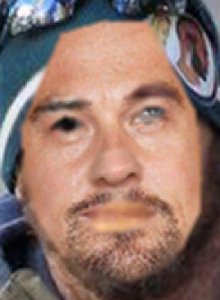

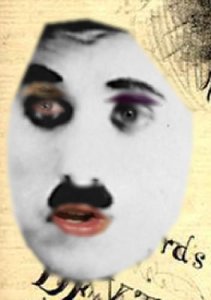

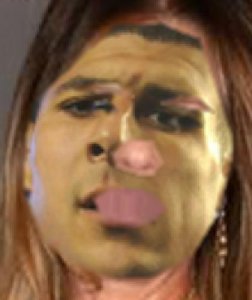

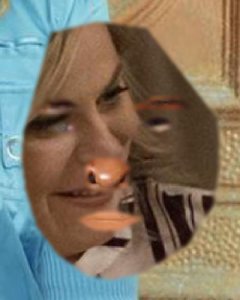

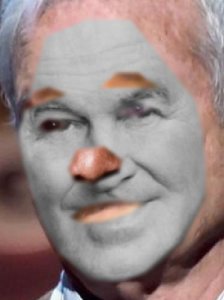

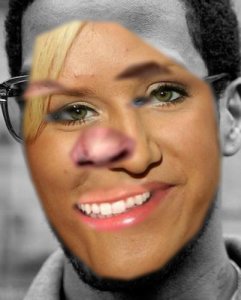

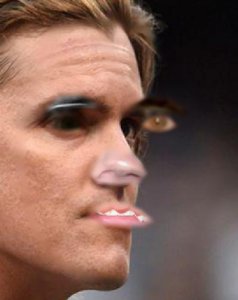

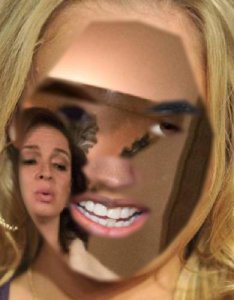

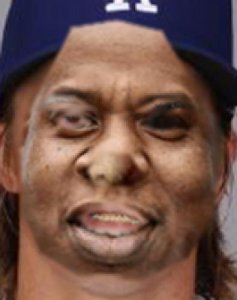

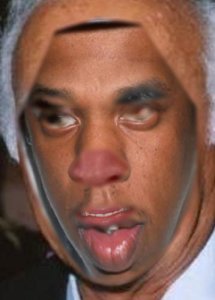

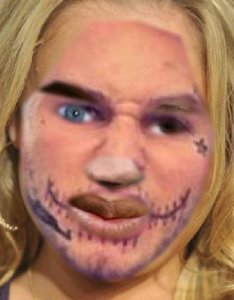

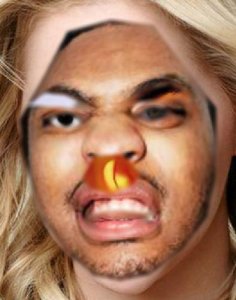

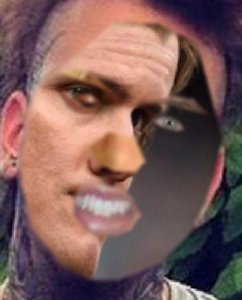

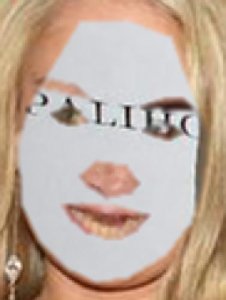

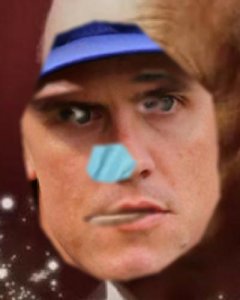

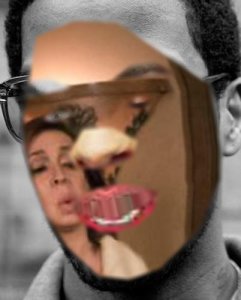

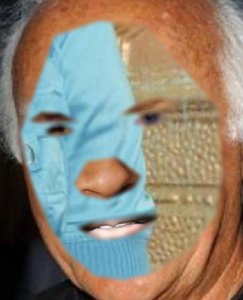

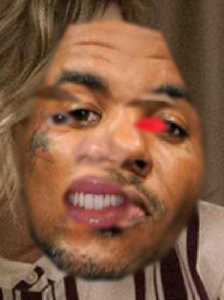

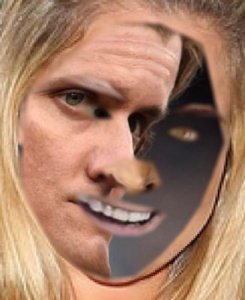

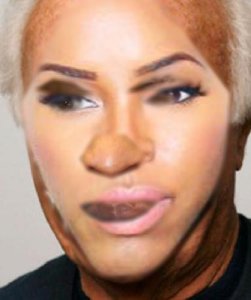

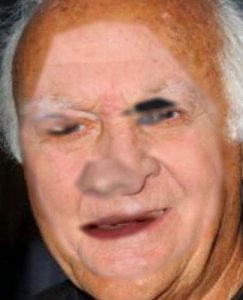

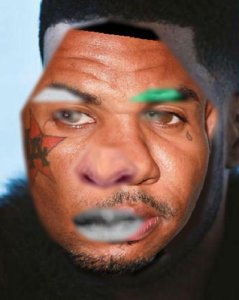

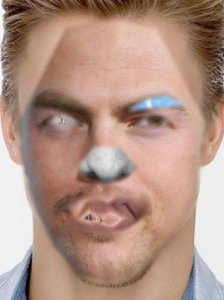

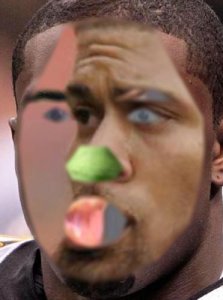

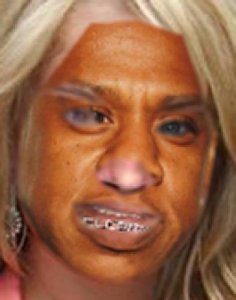

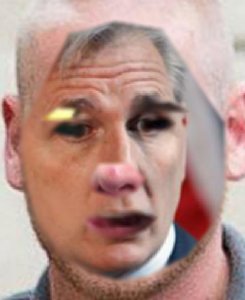

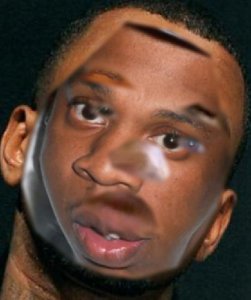

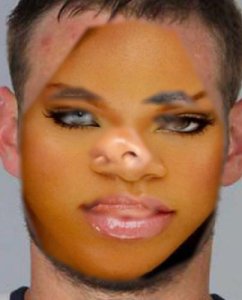

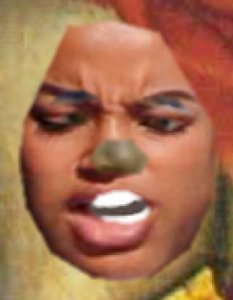

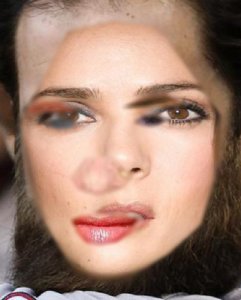

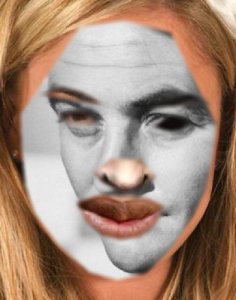

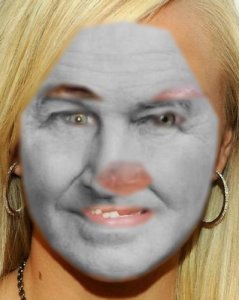

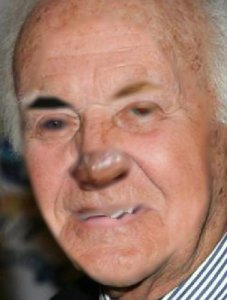

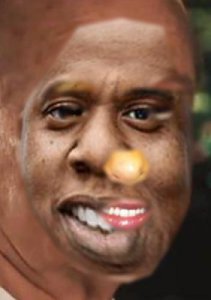

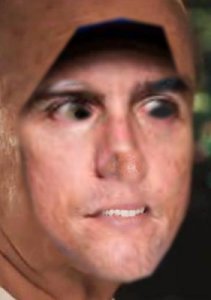

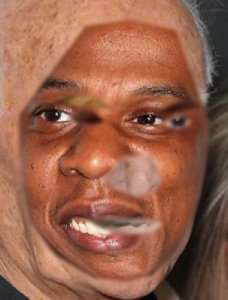

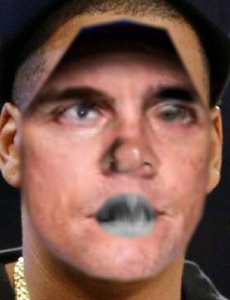

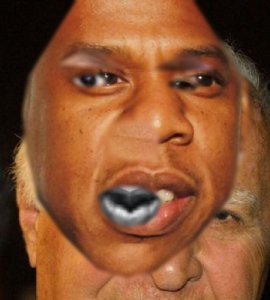

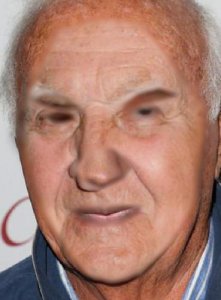

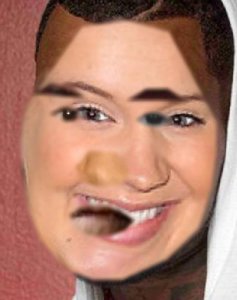

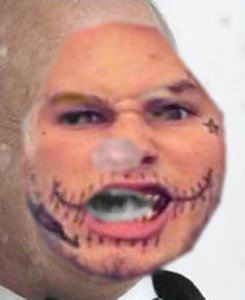

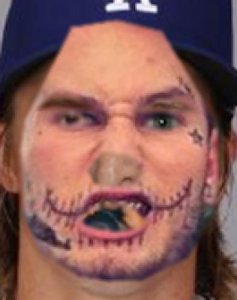

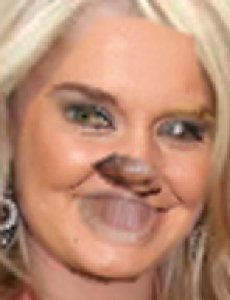

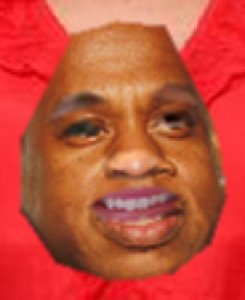

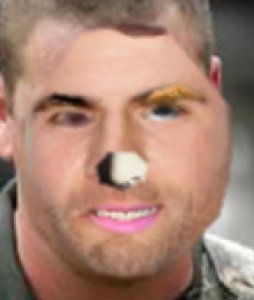

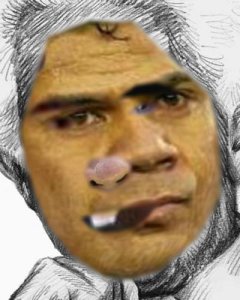

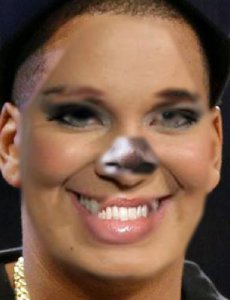

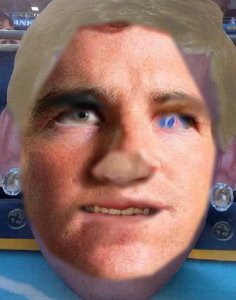

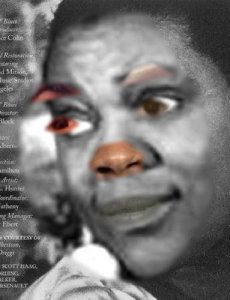

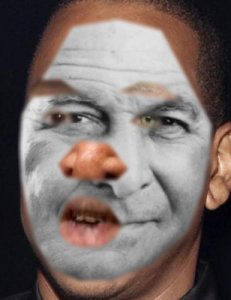

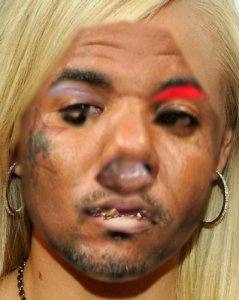

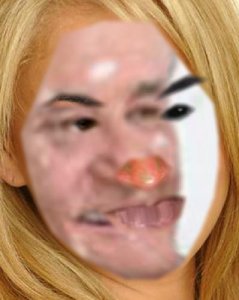

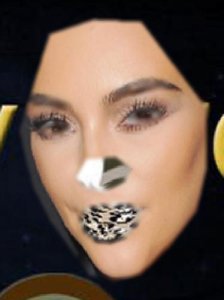

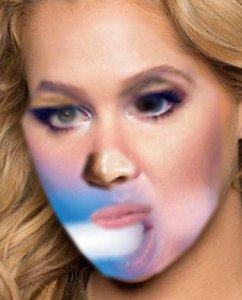

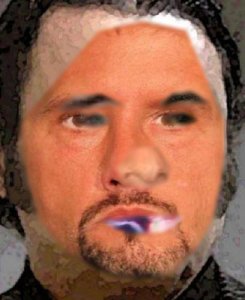

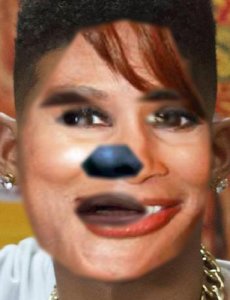

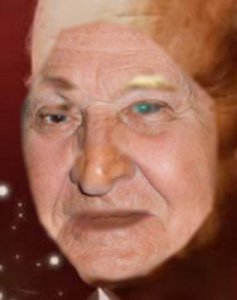

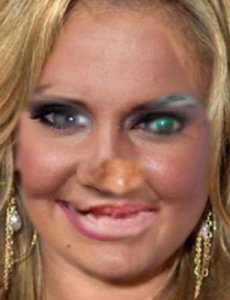

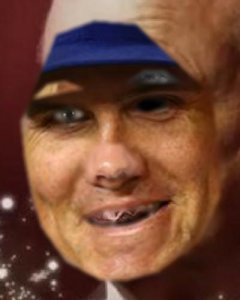

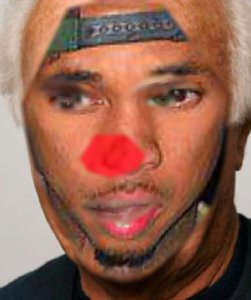

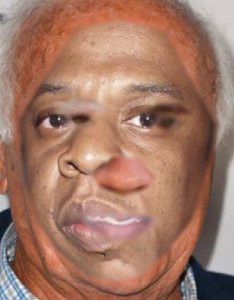

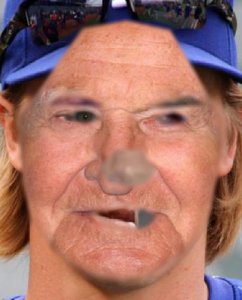

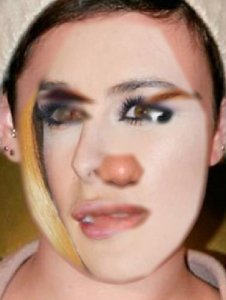

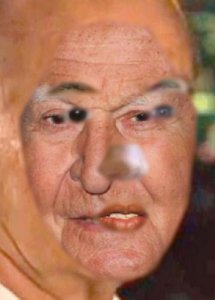

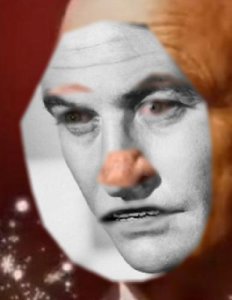

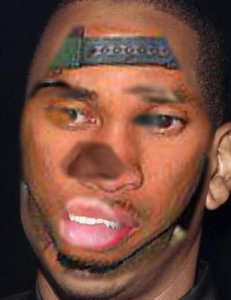

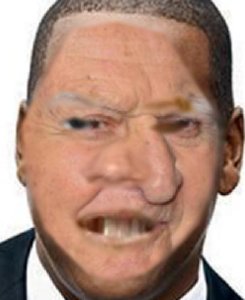

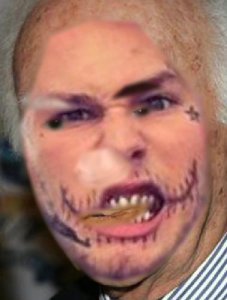

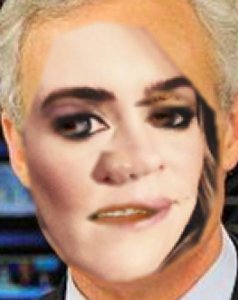

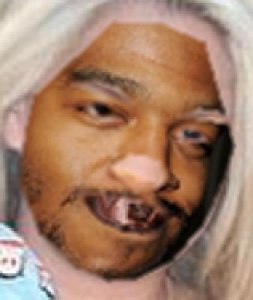

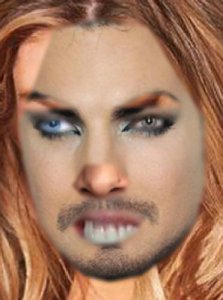

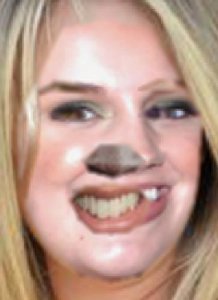

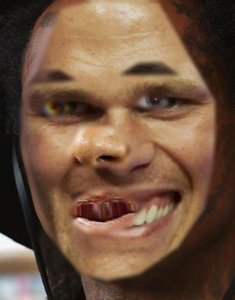

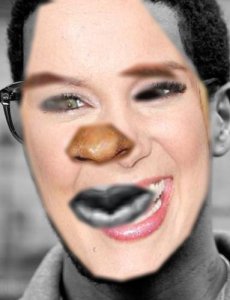

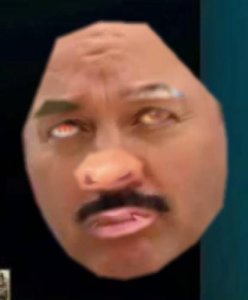

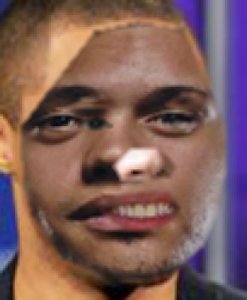

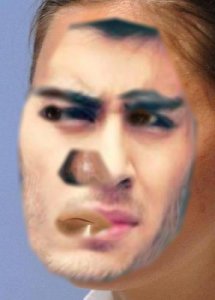

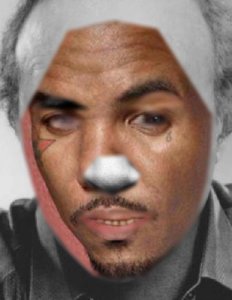

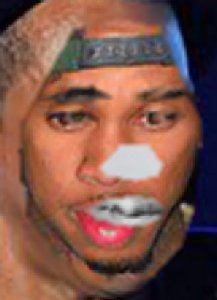

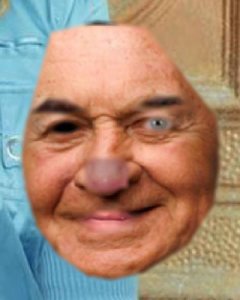

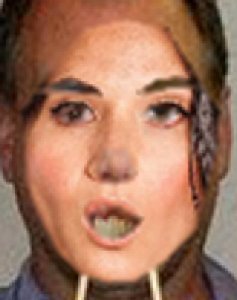

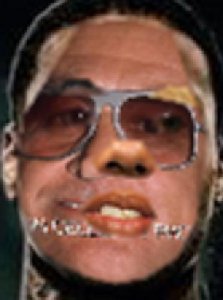

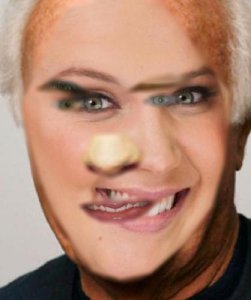

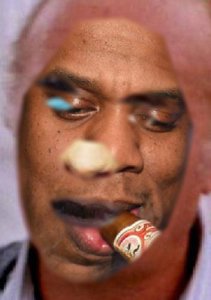

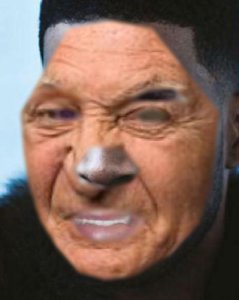

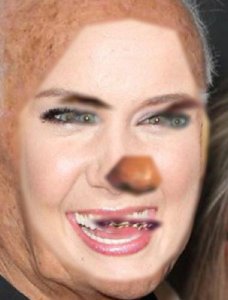

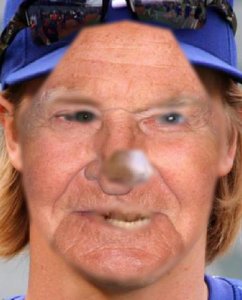

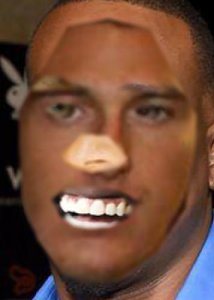

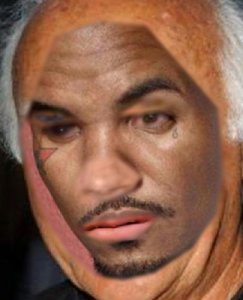

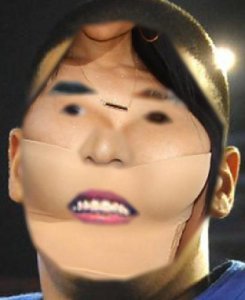

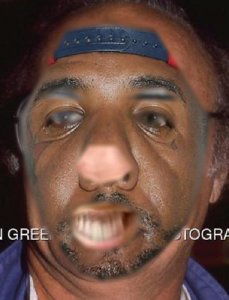

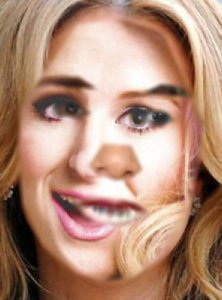

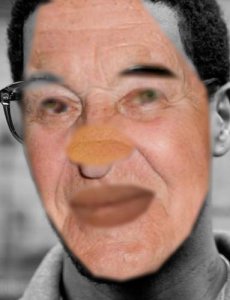

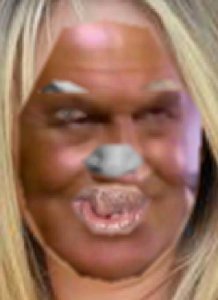

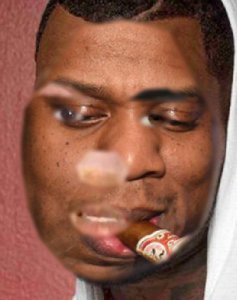

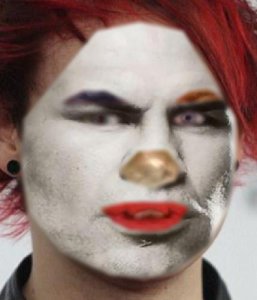

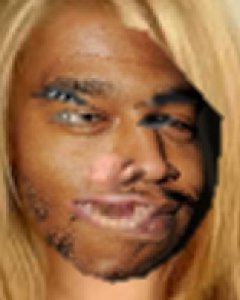

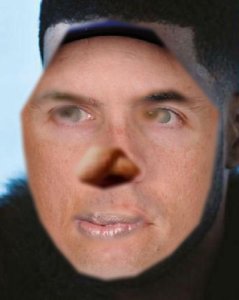

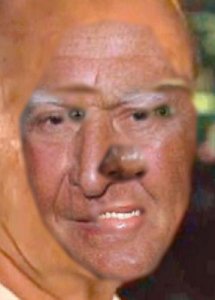

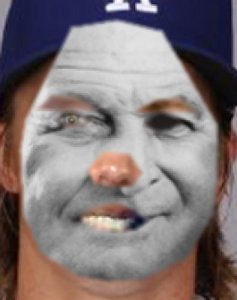

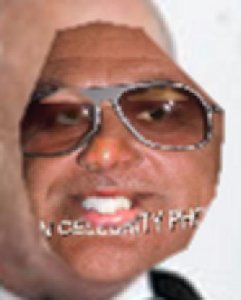

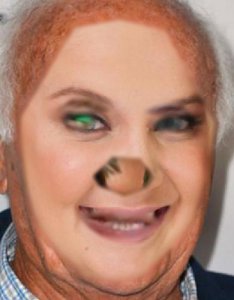

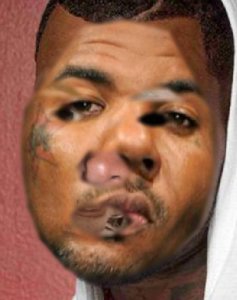

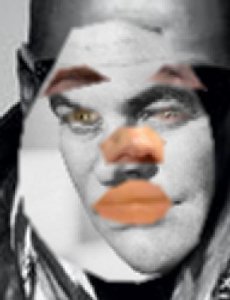

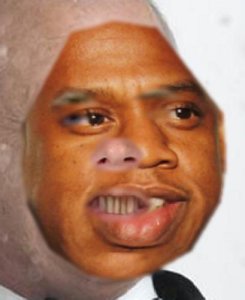

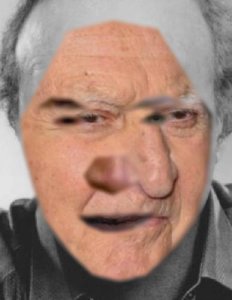

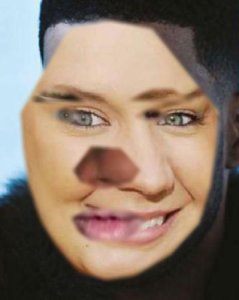

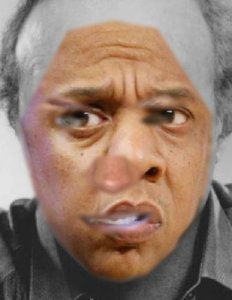

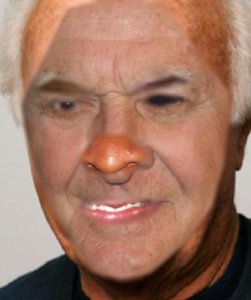

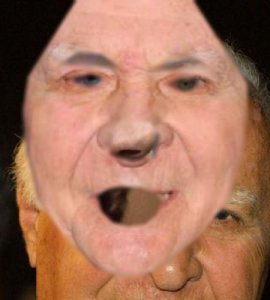

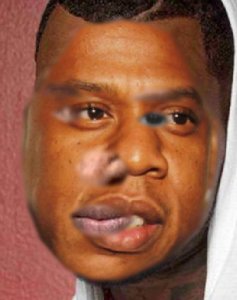

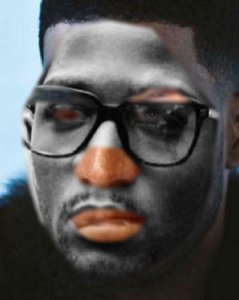

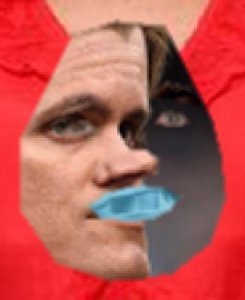

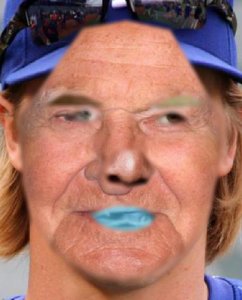

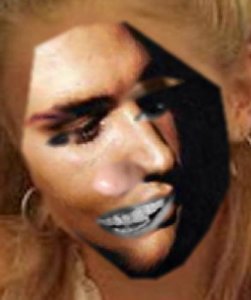

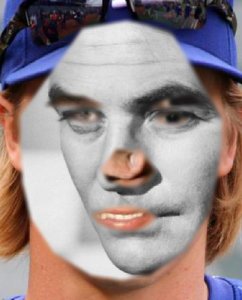

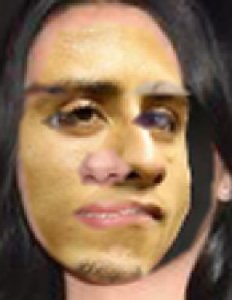

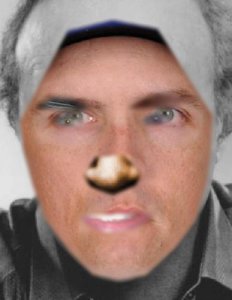

Recognised Faces is an internet application by Kristoffer Ørum that ran for a year. Each day, the system generated a new composite face from images found via Google’s lists of top search terms. Facial features in the collected images were identified using Stasm, an open-source software package for facial recognition originally developed for biometric applications. Stasm detects the position of 77 facial landmarks on upright, front-facing human faces with neutral expressions. These landmark positions were then used to align, cut and combine eyes, noses, mouths and jawlines into a new synthetic portrait.

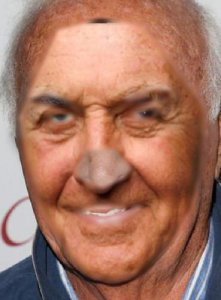

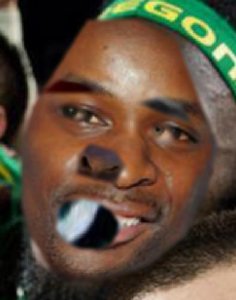

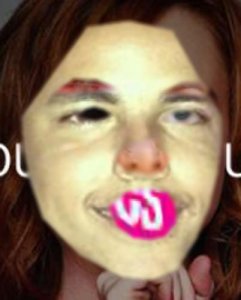

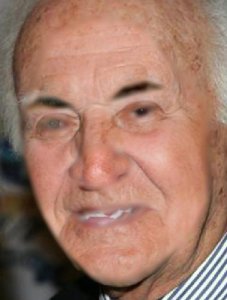

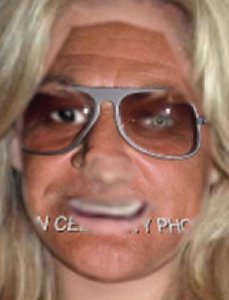

Once generated, these daily phantom faces replaced Ørum’s personal avatar across his website, social networks and other platforms. By reinserting them into the same online environments where facial recognition is used for surveillance, marketing and classification, the project subtly disrupted how automated systems construct a digital identity.

By constructing new faces from parts of the most widely circulated images online, Recognised Faces created a snapshot of the constant data collection and algorithmic recognition happening daily on the internet. The resulting images visualise how computers perceive individuals not as whole people but as patterns within datasets. Fed back into the internet, these phantom portraits acted as a small disturbance within systems of profiling maintained by intelligence agencies, corporations and other data collectors.

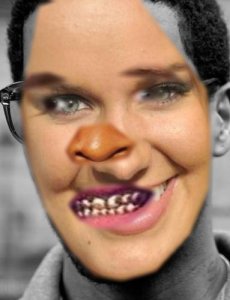

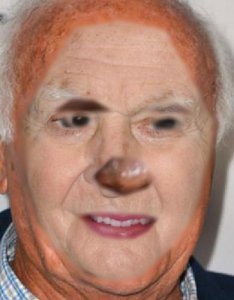

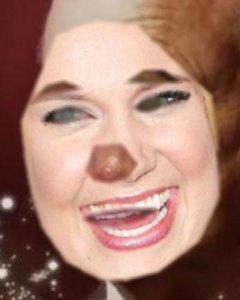

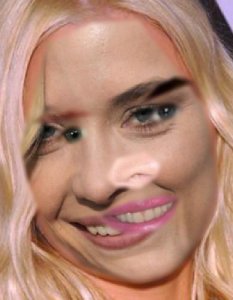

The faces produced through this process often appear distorted or uncanny to human eyes, yet they retain a resemblance to mainstream ideals of beauty. What looks like a glitch to humans is in fact a trace of the statistical modelling that drives the software. This duality exposes both the shortcomings of surveillance technologies and the alternative forms of perception they enact, offering a mechanical way of seeing that highlights aspects of our species that human vision alone might overlook.

Recognised Faces unfolded publicly on a dedicated Tumblr, where the daily composites accumulated into a year-long portrait of both an individual and the internet’s visual culture at large. The project has been discussed in Vice and elsewhere as a reflection on surveillance, aesthetics and identity in the age of algorithmic vision.