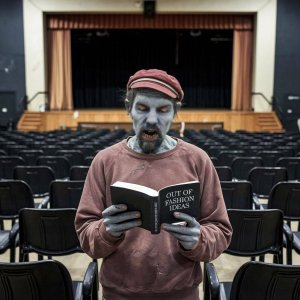

Project Details

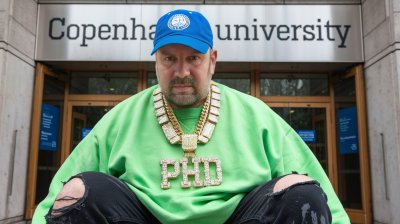

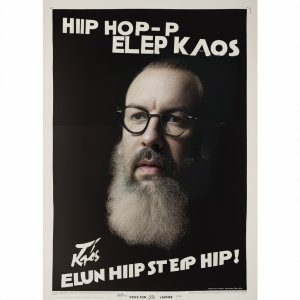

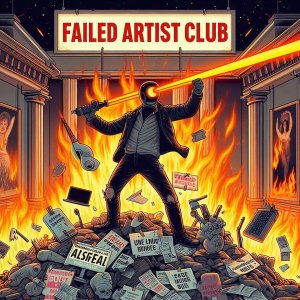

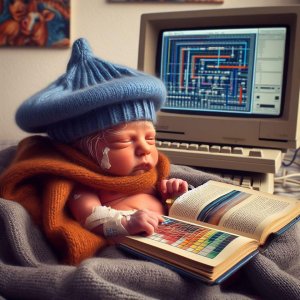

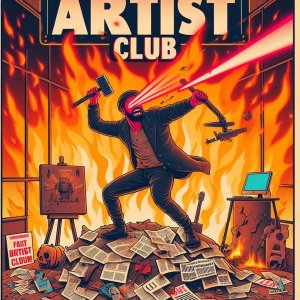

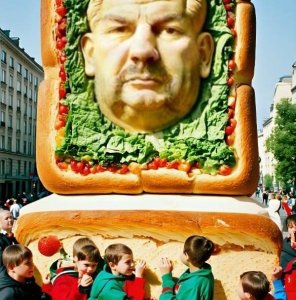

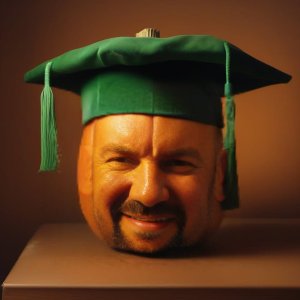

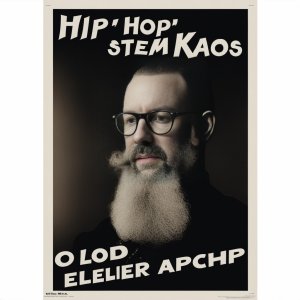

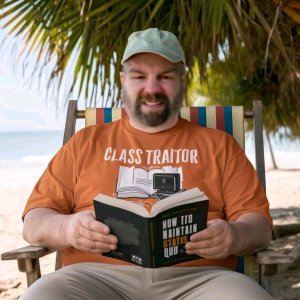

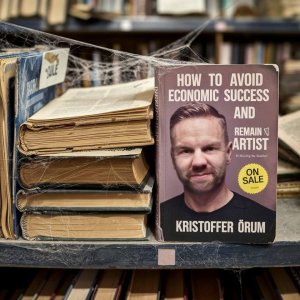

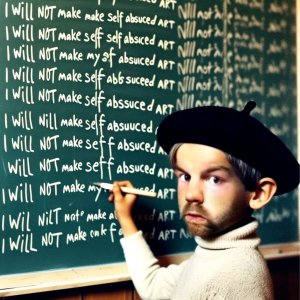

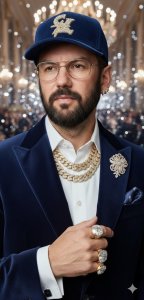

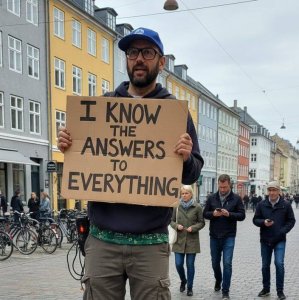

None of these images are of me.

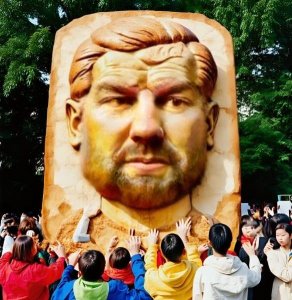

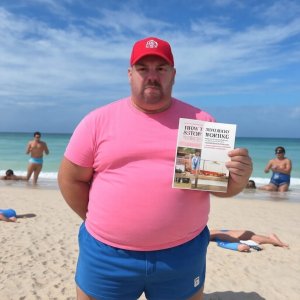

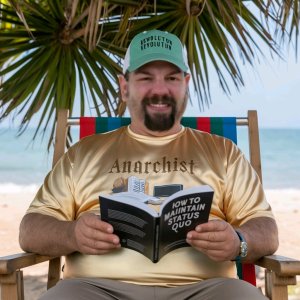

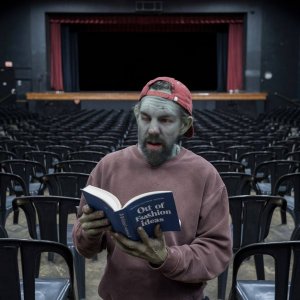

Over the past year, I have created a series of self-portraits using locally run AI. They function as my avatars on social networks in an ongoing performative investigation. The fact that they are made with local AI is important, because it provides a certain independence from the major platforms and makes it possible to work with the technology on my own terms.

Why create images that place myself in problematic and humorous situations?

I do it because I see a critique of the world that too often points outward, as if one could speak from a neutral and elevated place. Philosopher Donna Haraway has called this illusion a “god trick”: a view from nowhere that claims to see everything. I do not believe in this. Like Haraway, I believe the only honest critique must come from a situated place—knowledge that is always embodied, compromised, and grounded in specific contexts.

I also do it because local AI is itself an impure position. On the one hand, it can be seen as an attempt to resist the grip of major platforms, their data collection, and their opaque models. Running small, open systems on one’s own hardware provides a degree of autonomy and technological self-determination. On the other hand, these systems are still trained on global datasets full of bias, stereotypes, and inequality. The hardware is produced through resource-intensive processes, and even the “local” is entangled in a global infrastructure. It is not pure resistance, but rather an example of how critique and complicity inevitably coincide.

I also do it because I, as a white, established, middle-aged male artist, embody many of the privileges and blind spots that shape both the world and the art world. In line with Andrea Fraser’s insistence on self-involvement, it is not about attacking the institution from the outside, but about recognising that “we are the institution.” My privileges, desires, and limitations are not individual flaws, but embedded expressions of the systems I rely on. When I use myself as material, my body and my image become a site for institutional self-critique—where paradoxically critique and complicity overlap.

I am also tired of a “call-out” culture that too easily becomes hostile and makes it difficult to build the broad alliances we need. Call-outs have of course played an important role in making injustices visible, but when they are based on an idea of moral purity, they also create distance. I believe a stronger foundation for community lies in a shared recognition of vulnerability. As Judith Butler has pointed out, an acknowledgement of our interdependence can be a basis for political communities, while Sara Ahmed highlights the possibility of an “affective solidarity” built on honesty rather than claims of innocence. This does not mean that vulnerability is shared equally—some bodies are more exposed than others—but that we might begin in a recognised mess rather than in ideals of purity.

Humour also plays a role. I do not see it as the opposite of critique. On the contrary, humour often arises in breaks with the expected, in encounters with the unknown, bringing fear and laughter close together. In art and activism, humour has repeatedly functioned as a way of exposing the absurdity of power—from Dadaist performances to contemporary meme cultures. Instead of creating harmonious, utopian micro-topias, as some socially engaged art has sought, my images search for what Claire Bishop has called “relational antagonism.” They are meant as small frictions that create discomfort, opening up truths we would rather repress about the codes of the art world and our place within them.

AI makes it possible for me to be several people at once. This breaks with the idea of a coherent and authentic artistic subject—an illusion that the art market is still deeply dependent on. Yet it is also a paradox: even though AI produces many versions of me, they all point back to a recognisable “I.” This double movement—dissolution and reinforcement—is part of what interests me. As Rosi Braidotti has written, critique of the “tyranny of the unified subject” cannot be separated from the fact that we constantly reproduce the very idea of it.

The art world overflows with images of beautiful, smart, and confident artists. These images are not neutral. They draw on the advertising industry’s most simplified identity categories and support algorithmic preferences. They contribute to a narrowing of bodily representations that is far more damaging in the long run than strange AI slippage. I miss images that are weird, flawed, or personal.

I am also tired of so-called critical art being presented through the same visual culture as fashion: the artist in their beautiful home, in front of their impressive bookshelf, or in their picturesque studio. At the same time, I know how effective these images are. I participate in the system myself because it can grant me access to freedom and resources. Admitting this is not, in Andrea Fraser’s spirit, a defeat, but a strategy: I would rather acknowledge my own narcissism and greed and use them as material, than pretend I stand outside.

I believe that vulnerability and the recognition of one’s own inadequacy can create stronger communities than ideals of moral purity. I am tired of artists who speak as if they know what is best for others, instead of investigating what is wrong with themselves.

I make portraits because I would like to avoid them, but I know they are part of the game on which I depend. And I want to acknowledge that. None of us escape this system by pretending we are not part of it. Perhaps there is more hope in admitting how deeply we are all entangled.

None of these images are of me. And yet, they are all in part true.